Thanks to ASC Incubator, Local Artists are Ready to Go Public

By Page Leggett

Making art for the public sphere can lead to regional, national and even international recognition. It’s also potentially lucrative.

But it involves much more than artistic talent.

Artists must know how to manage budgets, work on a grand scale and collaborate with business leaders, government officials and the public.

And no one teaches artists how to do any of the above. They have to learn by experience.

That is until the Arts & Science Council (ASC) introduced its inaugural Going Public: A Public Art Incubator cohort. The program, a collaboration with Lowe’s, is designed to equip professional artists with the skills necessary to become competitive candidates for public art projects.

ASC put out a call to artists, and representatives from ASC and Lowe’s reviewed submissions, which included resumes and portfolios, and chose eight participants. “We wanted the group to be diverse in gender, sexual orientation, background, medium, work experience,” said Todd Stewart, ASC’s vice president of public art. “There was no prerequisite to have experience with public art – just a great interest in learning about it.

“It’s really not until you start making public art that you understand the process – through trial and error. No boilerplate process works well for every artist and every project. I wanted to our cohort to hear first-hand from artists who’ve walked this path.”

Each workshop – there were three – had an artist facilitator who had either completed public art projects, or was in the process of managing a project, for ASC. Stewart and Program Director Randella Foster kicked off each meeting before turning it over to the guest artists.

Artists who went through the inaugural cohort are:

- Maria Velez Campagna, who works in a variety of media including acrylic, watercolor, digital and fiber arts.

- Jonathan Grauel, who uses energetic lines, whimsical shapes and vivid color to construct surreal spaces.

- Jinna Kim, a multidisciplinary artist, filmmaker and playwright

- Oliver Lewis, who creates installations that engage the public in the principles of science and mathematics

- Nadia Meadows, a sculptor, multidisciplinary and visual storyteller whose work facilitates intercultural exchange

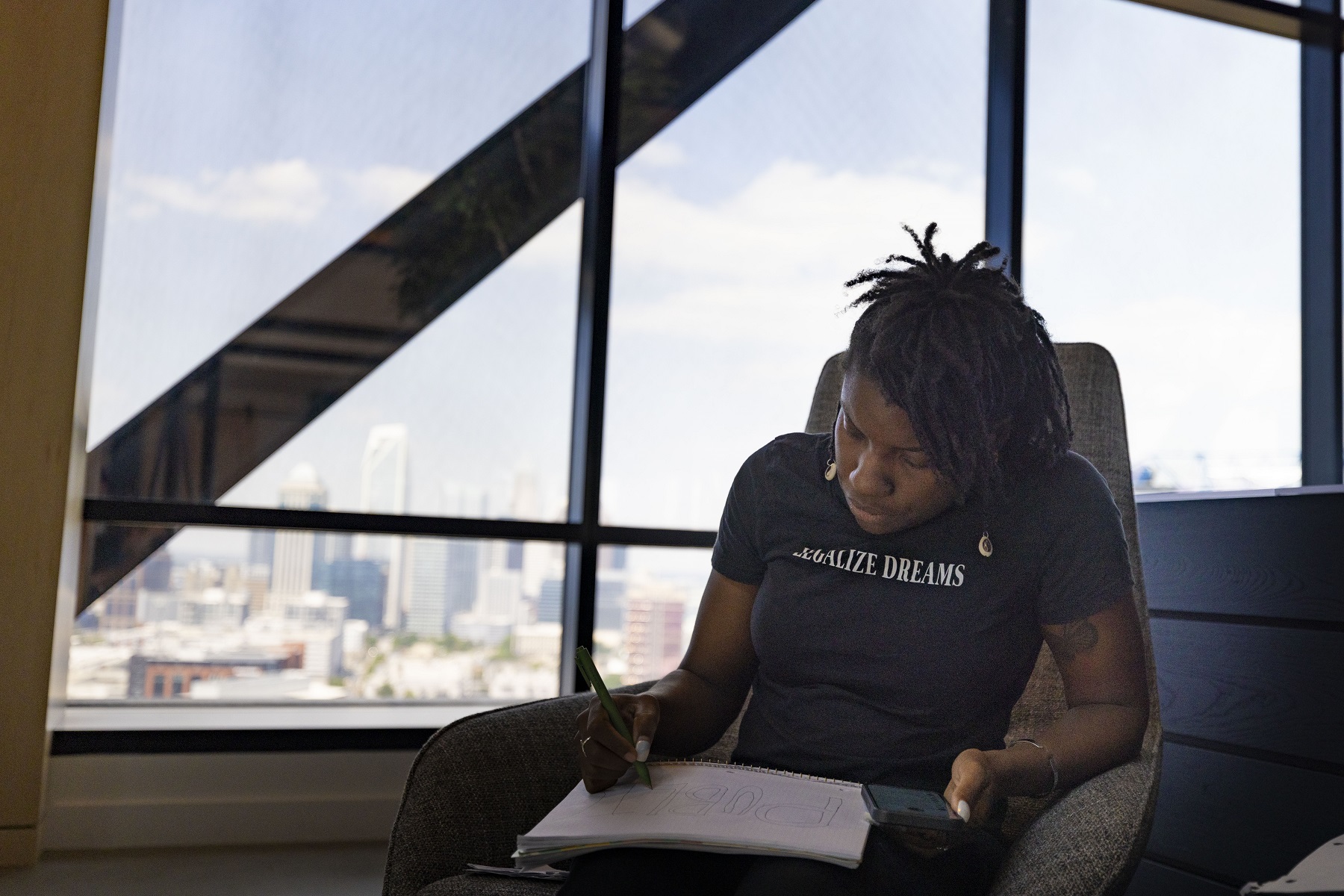

- Unique Patton, whose art examines relationships, empathy, faith-based and cultural experiences

- G. Scott Queen, a research and conceptual artist who creates physical and virtual works of art from a technologist’s perspective

- Thomas Schmidt, whose abstract works capture moments of chance and imperfection that embody the human experience

Understanding the complexities of public art

Nadia Meadows’ materials vary depending on what she’s trying to say with her art. They include wood, metal, paint and even human hair. (“Everyone has a hair story,” she said.) She’s created temporary public art installations – for Charlotte Shout!, for instance – but hadn’t applied for a permanent public art installation. (She has now.)

Meadows’ biggest surprise of the program was “finding out that public art projects can take years to come to fruition.”

That shocked Maria Velez Campagna, too. An artist told them he’d been working on one project for about four years.

“He’d nearly finished fabricating it, but the site wasn’t ready, so he had to find somewhere to store it,” she said. “And this work can be huge. There can be a lot of different factors that cause a project delay, especially in new construction.”

Knowing the potential pitfalls doesn’t make her less inclined to pursue public art opportunities. (In fact, she already has.) But she’s grateful to have had her eyes opened.

Meadows’ biggest takeaway was the importance of building a team – something she’d never had to consider. “As an artist, I’m used to working alone in my studio,” she said. “But with public art, you need a team of designers, fabricators, installers.”

Still, she’s undaunted. She recently applied for her first public art commission. She learned about the application process during the program and also learned “the right questions to ask before considering what to make. You have to get to know the community; you have to connect with them and use the information you get to inform your work,” she said.

Campagna, too, appreciated learning how to collaborate with the public.

“When using public funds, it’s not about being in your studios; it’s about finding what the community wants and executing that in an artistic way,” she said. “We talked a lot about how to do community engagement, what to expect when you go before a city or town council or neighborhood association. You have to consider how you’ll do it – in person? With technology, such as online surveys?”

She finished the program knowing “some projects don’t go the way you expect – especially with new construction.”

Even public art veterans learned something

Scott Queen has been making public art since college. Today, he’s part of ASC’s Regional Artist Directory, which means he’s pre-qualified to design or build creative features for city, county and private projects that may or may not be associated with larger scale public art projects with budgets under $85,000.

“I had some experience in education, project management, public artmaking. I know how to work a budget,” he said. “But I lacked understanding of how you engage communities.”

Queen said the cohort’s focus on managing large budgets has given him “an edge [he] didn’t have before.” And he now knows about what can go wrong during the often-protracted process. “We got to ask artists tough questions like: ‘What was the biggest thing you failed on?’ And they were willing to tell us.

“The main value, for me, was the insight into how to approach the artmaking practice with business in mind.”

The curriculum

The program was divided into three parts:

- “Answering the Call to Artists: Applying for Opportunities” was led by Stacy Utley, “an amazing artist within the studio and through his public work,” said Stewart. “He has one of the most polished presentations of any artist; we were really lucky to have him.”

Each session ended with a hands-on activity, which Stewart said, “was a way of immediately putting into practice what we’d talked about.” At the first session, they held a mock artist selection panel and evaluated (anonymous) applications to a call for public art. “They got to come to their own decisions,” Stewart said. “They discovered what it’s like to be on the other side.”

- “Public Art is a Team Sport” focused on community engagement. Artist, architect and UNC Charlotte professor of architecture Rachel Dickey “conducted one of the most thoughtful and intentional creative community workshops I’ve ever participated in,” Stewart said. “She talked through what it means to involve other people in the creative process, what it means to be a good collaborator.”

The cohorts were tasked with creating a strategy for community engagement designed to elicit specific input. Then, they held practice sessions and reviewed strategies to deal with inevitable criticism and feedback.

- Sculptor Shaun Cassidy, a Winthrop University professor, led “Making Project Measurements.” “He has so much experience in public art,” Steward said. “It was a no-brainer to bring him to walk through the good, the bad and the ugly. He brought up the challenges every artist should be aware of.”

That session concluded with a site visit to an ASC-led public art project.

Participants took away from the experience what Stewart hoped they would. “Anyone interested in being a public artist has to know how to be a good collaborator, bring people along in their process and when to compromise. All public art involves some level of compromise.”